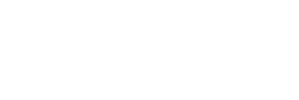

Corporate finance is the backbone of any business, covering everything from managing day-to-day operations to making strategic, long-term decisions. While introductory courses focus on core concepts like capital budgeting, working capital management, and financial statement analysis, the world of corporate finance extends into more complex and specialized areas. These advanced topics are critical for finance professionals, executives, and investors who seek to understand how firms create, manage, and distribute value in an increasingly complex global marketplace.

1. Capital Structure Theory and Optimal Capital Structure

A fundamental question in corporate finance is: what is the best mix of debt and equity to fund a company’s operations? This is the essence of capital structure theory. The goal is to find the optimal capital structure—the combination of debt and equity that minimizes the company’s cost of capital and maximizes its market value.

The journey to understanding this started with the groundbreaking work of Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller (MM). Their famous MM Theorem proposed that, in a perfect market with no taxes, bankruptcy costs, or information asymmetries, a company’s value is independent of its capital structure. This counterintuitive idea set the stage for later research, which introduced real-world complexities.

- Trade-Off Theory: This theory acknowledges that debt provides a tax shield—interest payments are tax-deductible, reducing a company’s tax liability. However, this benefit is offset by the increasing costs of financial distress, such as bankruptcy costs and agency costs, as a company takes on more debt. The optimal structure is a balance where the marginal benefit of the tax shield equals the marginal cost of financial distress.

- Pecking Order Theory: This theory, proposed by Myers and Majluf, suggests that companies prefer to finance their investments using internal funds first (retained earnings). If external funds are needed, they prefer to issue the safest securities first, which is debt, before resorting to equity. This behavior is driven by information asymmetry—managers know more about the company’s prospects than outside investors. Issuing equity can signal that a company is overvalued, as managers would only do so if they believe their stock is expensive.

2. Real Options Analysis

Traditional capital budgeting methods, such as Net Present Value (NPV), assume a passive investment strategy. They calculate the value of a project based on a single set of cash flow projections. However, in reality, managers have the flexibility to make decisions during the life of a project. This flexibility is what real options analysis captures.

A real option is the right, but not the obligation, to take a future action. Much like a financial option, these options have value. Common real options include:

- Option to expand: The ability to scale up a project if it is successful.

- Option to abandon: The right to shut down a project if it is performing poorly, limiting losses.

- Option to wait: The flexibility to delay an investment until more information is available or market conditions are favorable.

By valuing these options, a company can get a more accurate picture of a project’s true worth, often finding that projects with a negative traditional NPV might actually be valuable due to the embedded flexibility.

3. Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) and Corporate Restructuring

M&A is one of the most dynamic and complex areas of corporate finance. It involves the acquisition of one company by another or the consolidation of two companies into one. While the strategic reasons for M&A are numerous—achieving synergies, gaining market share, or diversifying risk—the financial mechanics are what corporate finance professionals analyze.

- Valuation: A critical step in any M&A deal is valuing the target company. This goes beyond simple multiples and involves advanced techniques like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis, comparable company analysis, and precedent transaction analysis. The ultimate goal is to determine a fair price that creates value for the acquiring company’s shareholders.

- Synergy Valuation: The key driver of M&A value is the creation of synergies, which are the benefits that arise from combining the two companies. These can be cost synergies (e.g., economies of scale, eliminating redundant operations) or revenue synergies (e.g., cross-selling, expanded market reach). Valuing these synergies is often the most challenging part of the process, as they are based on future projections and assumptions.

- Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs): An LBO is a specific type of acquisition where a company is purchased using a significant amount of borrowed money. The assets of the acquired company are often used as collateral for the loans. Private equity firms frequently use LBOs, aiming to improve the company’s operations, reduce costs, and then sell it for a profit after a few years. Understanding the complex debt structure and cash flow implications is crucial for analyzing LBOs.

4. Behavioral Corporate Finance

Traditional corporate finance assumes that managers and investors are rational actors who make decisions to maximize shareholder value. Behavioral corporate finance challenges this assumption by incorporating insights from psychology and sociology to explain real-world financial decisions.

This field explores how cognitive biases and heuristics affect corporate decisions. For example:

- Overconfidence: Managers may be overconfident in their abilities, leading to value-destroying acquisitions or overly optimistic project forecasts.

- Herding behavior: Managers may follow the actions of their peers, leading to a wave of similar decisions (e.g., a flurry of acquisitions in a specific industry) that may not be individually rational.

- Loss aversion: Managers may be reluctant to abandon failing projects, even when it’s financially prudent, due to a strong preference to avoid realizing a loss.

By understanding these biases, companies can design better governance structures and decision-making processes to mitigate their negative effects.

5. International Corporate Finance and Currency Risk Management

In a globalized economy, companies often operate across borders, exposing them to a new set of financial risks and opportunities. International corporate finance focuses on these unique challenges.

- Foreign Exchange (FX) Risk: Companies that do business in multiple currencies face currency risk. A sudden, unfavorable change in exchange rates can erode the value of international revenues or increase the cost of foreign inputs. Finance professionals use tools like forward contracts, options, and swaps to hedge against this risk.

- International Capital Budgeting: Valuing an international project is more complex than a domestic one. It requires forecasting foreign cash flows and then converting them back to the home currency using projected exchange rates. The discount rate must also account for the political and economic risks of the foreign country.

- Political Risk: Operating in foreign countries exposes a company to political risks, such as expropriation of assets, changes in tax laws, or restrictions on repatriating funds. Evaluating and mitigating these risks is a key part of international corporate finance.

Conclusion

Advanced topics in corporate finance move beyond the basics to address the complexities of a dynamic business world. Understanding capital structure, real options, the intricacies of M&A, the impact of behavioral biases, and the challenges of international finance allows professionals to make more informed, strategic decisions. These areas of study not only enhance a firm’s ability to create and manage value but also provide a deeper understanding of the forces that shape financial markets and corporate strategy. For anyone looking to excel in finance, delving into these advanced concepts is not just beneficial—it’s essential.